Ubuntu: I Am Because We Are

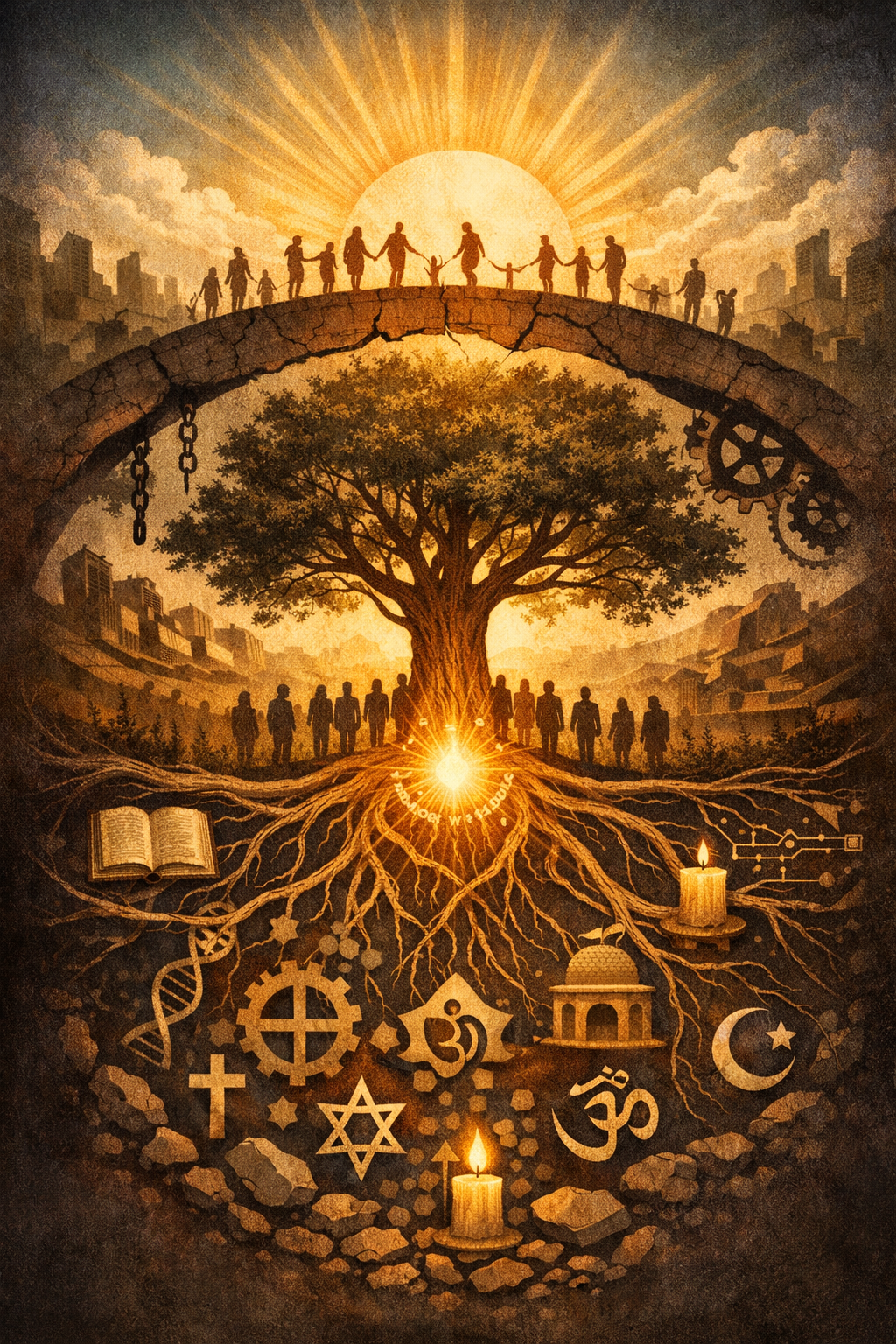

The word comes from southern Africa. But the truth it carries is older and wider than any single language. It appears in the Rumi's poetry and the Sikh Gurus' lives. In the Kabbalists' repair work and the Taoists' effortless action. In Buddhist restraint and Thomistic participation. In the Sufi's submission and the Animist's listening. Different traditions. Different centuries. Different metaphors for the same shape: the self cannot cohere alone. The "we" is not optional. Coherence is relational all the way down. Ubuntu is not new wisdom. We are always rediscovering it because we keep forgetting it. And each time we remember, it feels like discovery—when really, we've just stopped pretending we don't already know.

There is a kind of truth that feels too simple to be profound.

So simple that it sounds like a bumper sticker. So obvious that you assume it must be a summary of something deeper, a slogan standing in for a theory you haven’t studied yet. And because it looks small, we step over it.

Ubuntu is one of those truths.

“I am because we are.”

That’s it. That’s the whole sentence. It doesn’t ask for qualifications. It doesn’t come with footnotes. It doesn’t offer you a system to join or a doctrine to defend. It just points to something you already know, if you’ve ever been human for more than five minutes.

And yet we live as if it isn’t true.

We build institutions as if people are interchangeable parts. We build careers as if we are lone protagonists. We build technologies as if “users” are abstractions. We build identities as if they are private property. We build wealth as if it can be separated from the web that made it possible. We build safety as if it can be achieved alone.

Then we act surprised when the world starts to feel lonely, brittle, and hostile. We wonder why meaning feels thin. We wonder why trust collapses so quickly. We wonder why everyone seems so tired.

Ubuntu is not a moral instruction. It is not telling you to be nice. It isn’t asking you to sacrifice yourself to the group. It isn’t proposing a political program.

It’s describing the topology.

It’s telling you how the world is wired.

A human being is not a sealed container that occasionally exchanges messages with other sealed containers. A human being is a node inside a living fabric. You do not merely interact with the fabric. You emerge from it. Your sanity is partly borrowed. Your language is inherited. Your values are shaped in relationship. Your confidence is stabilized by witnesses. Your identity is not a thing you own. It is a pattern you enact, repeatedly, in the presence of other people.

Even the idea that you are an “individual” is something you learned from a culture that was already there before you.

If you want to see how deep this goes, notice what breaks when the “we” breaks.

People don’t merely lose resources. They lose orientation.

They begin to doubt what is real, because reality is normally co-validated. They begin to lose motivation, because motivation is normally relational. They begin to lose character, because character is normally held in the friction of accountability and care. They begin to lose themselves, because the self was never a solitary construction project in the first place.

You can call this codependency if you want, but that’s just the modern nervous system trying to warn you about a real failure mode with the only language it has left.

Ubuntu isn’t codependency. It’s the opposite.

Codependency is what happens when the web becomes distorted, when relationship becomes manipulation, when care turns into control, when attachment becomes a substitute for integrity. Ubuntu is the clean version. The undisguised version. The relational ground before it’s been weaponized.

The reason we resist it is that Ubuntu destroys a fantasy that many of us have invested in for a long time.

The fantasy is that we can become coherent alone.

That we can optimize ourselves into wholeness. That we can have the benefits of community without the cost of being known. That we can accumulate wealth without being indebted to the structures and people that made accumulation possible. That we can “win” without anyone losing. That we can keep our options open forever without committing to a life.

This fantasy is not just naïve. It is corrosive. It produces an entire class of modern pathologies that we have become so accustomed to that we treat them as the price of being an adult.

Anxiety is what it feels like to be over-specified and under-held.

Depression is what it feels like when the web goes quiet and you begin to suspect the silence is telling the truth.

Performance is what it looks like when you have to manufacture signal because you don’t trust the relationship to carry it.

And the strange, exhausted nihilism that hangs in the air of modern life is often nothing more than a relational injury that was never named.

We speak about it in individual terms because that’s how our culture trains us to speak. We say “I am burned out.” We say “I have imposter syndrome.” We say “I’m not motivated.”

Sometimes that’s true, in the narrow medical sense. Often it’s also true in a deeper way.

Often what we mean is: I am trying to carry a load that was never meant to be carried by one person.

Ubuntu is the reminder that you were never supposed to.

There’s another reason Ubuntu feels dangerous to people. It seems to imply obligation.

If I am because we are, then I owe the “we.” I must surrender my autonomy. I must serve the group. I must accept whatever norms the collective imposes. I must become small.

This is how traumatized people hear the sentence. This is how captured systems want you to hear it. This is how cults and institutions try to translate it, because it gives them leverage.

But that is not Ubuntu. That is the counterfeit.

Ubuntu is not about surrendering the self. It’s about realizing the self was never an isolated project. The self is real, but it is not self-originating. It is not self-sustaining. It is not self-justifying. It exists in relationship, and it becomes coherent in relationship.

When you remove the “we,” the “I” doesn’t become free.

It becomes untethered.

This is why people who crave absolute independence often end up strangely fragile. Their entire identity is held up by continual rejection. Their strength is expensively maintained. Their sovereignty is not sovereignty at all. It’s a posture.

Real sovereignty is quiet. It doesn’t need to be announced. It is what happens when you can stand inside relationship without being swallowed by it, and stand alone without pretending you were never held.

Ubuntu doesn’t erase boundaries. It reveals why boundaries matter. A boundary is not a wall. A boundary is a membrane. It allows relationship without collapse. It allows exchange without invasion. It allows the “we” to exist without dissolving the “I,” and the “I” to exist without denying the “we.”

This is what mature systems do. The cells in your body do not merge into a uniform blob in the name of unity. They maintain membranes. They communicate. They specialize. They cooperate. They sometimes die so the organism can live.

They do this without ideology.

They do this because it’s how life works.

You can feel Ubuntu most clearly in the moments when it returns on its own, without anyone preaching it.

In a crisis, when people spontaneously coordinate without being told.

In a community that still knows how to show up for a funeral.

In the quiet relief of being seen by someone who doesn’t need anything from you.

In the strange warmth that follows an honest conversation that didn’t resolve anything, but made the relationship real again.

In the feeling of a small number of witnesses who know you well enough that you don’t have to perform your existence.

Those moments are not sentimental. They are infrastructural. They are the relational equivalent of clean data. They restore signal. They lower entropy. They make the world legible again.

And if you look closely, you’ll notice something else.

The “we” is not just people.

It’s also the systems you inhabit. The places you live. The institutions you touch. The technologies you build. The stories you tell. The practices you repeat. The rituals that hold you. The debts you refuse to incur. The memories you keep clean.

When you contribute to these things with integrity, you aren’t just being moral. You’re maintaining the fabric that maintains you. You are participating in something that will outlast you, whether or not anyone knows your name.

When you corrupt these things, the corruption does not remain external. It returns. Not always immediately. Not always dramatically. But reliably. It shows up as brittleness. As mistrust. As loneliness. As the need to control.

This is why “I am because we are” is not a feel-good quote. It’s a warning and a promise at the same time.

If the “we” rots, the “I” cannot remain intact.

If the “we” is tended, the “I” can become surprisingly free.

People sometimes ask how to “build community,” as if the “we” is a product you can manufacture if you follow the right playbook.

Ubuntu suggests something gentler and harder.

You don’t build the “we” by announcing it.

You build it by showing up with clean intent, over time, and refusing the small corruptions that make relationship unsafe.

You build it by not trying to be a savior or a deity.

You build it by being a person others can trust to keep the ledger clean.

You build it by choosing humility when you could have chosen dominance.

You build it by refusing to turn people into assets.

You build it by working yourself out of a job so the system can stand on its own.

You build it by making promises your future self can live with.

You build it by making your memory clean.

The funny thing is that once you start living this way, Ubuntu stops sounding like philosophy.

It starts sounding like a description of what you were doing all along, whenever you were at your best.

It becomes less of a concept and more of a recognition.

Of course I am because we are.

Of course I cannot be coherent in isolation.

Of course the path of a life is not just an individual story but a rendering witnessed by others.

Of course the smallest acts of care sometimes change everything, because they keep the fabric from tearing.

Of course the “we” is not optional.

We tried to pretend it was.

The results are all around us.

Ubuntu is the reminder we need not because it is complicated, but because it is simple enough to forget.

And if you let it land, it doesn’t burden you with obligation.

It relieves you of a fiction.

You were never meant to carry the whole world alone.

You were meant to become yourself inside a web of witnesses, and to leave the web a little cleaner than you found it.

That’s all.

That’s plenty.

That’s Ubuntu.